Last week, the students in my Shakespeare in Context course—the very same who are working their way through the Adopt-a-Book assignment I've written about here and here—spent a single 50-minute class period constructing a quarto of The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke (1603). (By the way, a 50-minute class period is a perfect amount of time for this activity.) This is not a book history course, even though (1) I use the textual histories of the plays to teach close reading; and (2) we study textual afterlives in order to think about the non-authorial agencies involved in creating "Shakespeare" over time and space.

I've been excited to see so many of my colleagues at other institutions (Piers Brown, Megan Heffernan, Aaron Pratt, to name a few) report back about how their classes fared with similar quarto-making activities and have been following along with great interest as my colleague Joshua Eckhardt's graduate seminar (re)creates a Virginia Company sermon from scratch in the VCUarts print shop.

Getting students to collate, fold, stab, and stitch a quarto out of 11x17 sheets created from EEBO printouts pales in comparison to this semester-long Virginia Company project and, for example, to the inventive ways in which Sarah Werner has taught book format in her undergraduate research courses at the Folger Shakespeare Library and through her blog. However, it's still a valuable activity in a course that aims to contextualize Shakespeare in his own time and over time, not least because it allows students to make their own observations about material practices while doing.

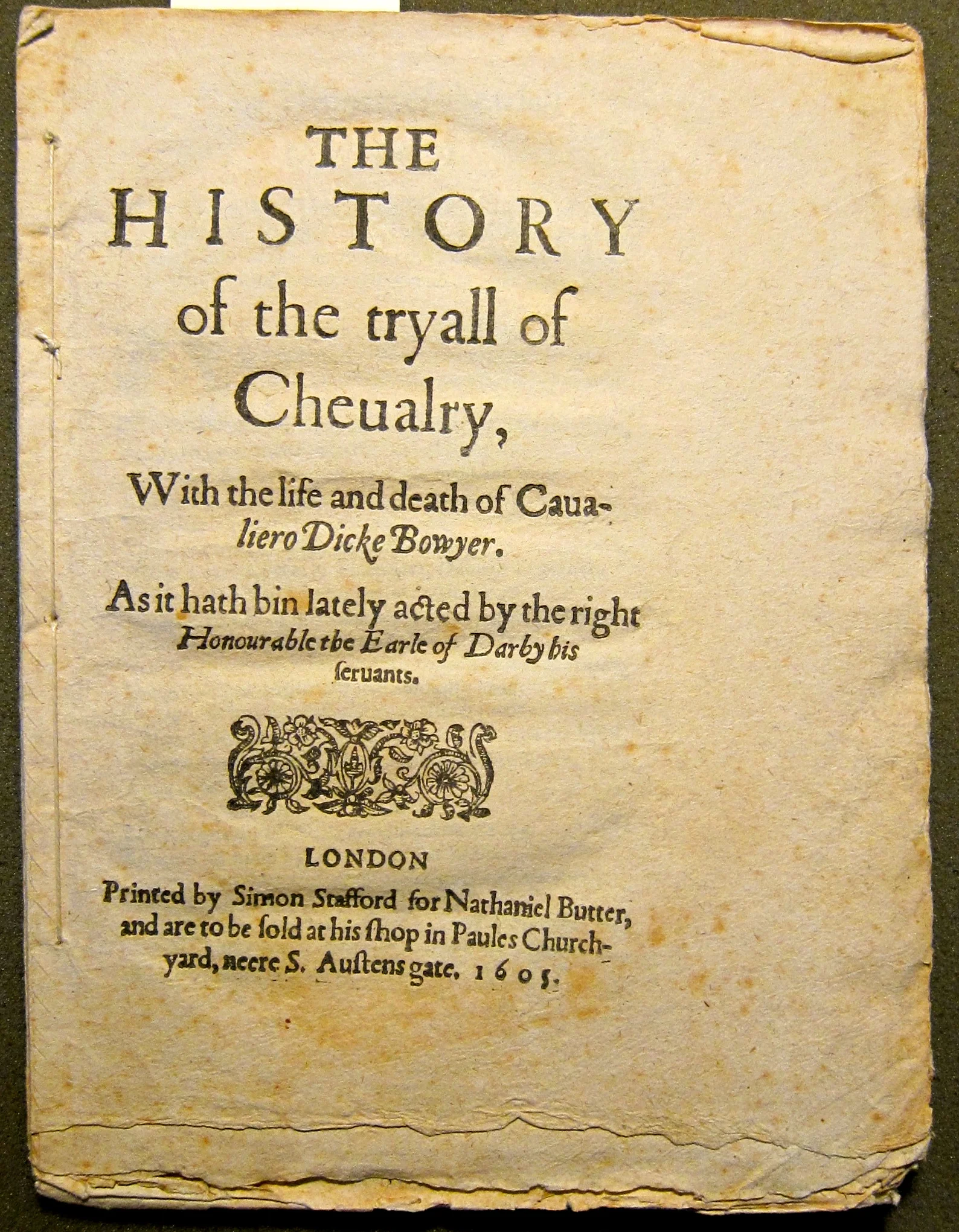

I gave my students almost no instructions for how to make the quarto, except to (1) show them a diagram of folio, quarto, octavo, &c, paper folding; (2) explain what catch-words were; and (3) provide them with images of the uncut, unopened, and stitched quarto of The Trial of Chivalry (1605, pictured). Then, with the assistance of VCU English MA student Julian Neuhauser, I put them to work in groups of three or four.

It took the groups about ten minutes to figure out how to use the catch-words and signature marks to fold the sheets correctly and sequence them from B to I. The first sheet proved to be a challenge, since it featured two "impressions" of the title page on the same sheet. Most groups came to the conclusion that they needed to cut the sheet in half and "discard" the other half. (When I do this again, I'll provide only half as many copies of this sheet so that the groups who get a copy of it will have to share their "discarded" copy of the title page with another group. This will better illustrate the principle of economy.) The next challenge was figuring out how to fold the usable half-sheet. Many groups wanted to wrap it around the other folded sheets like a dust jacket, while others wanted to fold it in half so that the title page was exposed. After some debate, we decided that it would make most sense to fold the half-sheet so the blank leaf came first as protection for the title page.*

Students were the most animated about the process as they attempted to stab-and-stitch the folded sheets together. They used awls that I'd bought at the local hardware store to bore holes through the paper. Then, they used binders' needles and thread that I found at the campus art supply shop to sew up the quarto. (Shop local!) There was a good deal of debate about how many holes they should make. Some groups imitated the Trial of Chivalry example by making four holes, while others opted for two or three.** Improvisation at its best!

When I asked the class to reflect on the process two days later, the first thing they wanted to discuss was the amount of manual labor it took to stab-and-stitch the gatherings together (and this is not to say anything of the labor required to run the printing press). This opened up a discussion about how all forms of textual production are both intellectual and physical: Shakespeare wouldn't be "Shakespeare" without the labor of those in the printing house and book stalls. While this may seem like an obvious point, it played as an ah-ha moment for students who have always received the texts of Shakespeare's plays as stable entities. In addition, deciding to fold the half-sheet containing the title page so the blank leaf came first spoke nicely to the ephemerality of print. This, in turn, allowed us to touch on the need for strategies of making the book-object more durable as well as collection and conservation practices that permit such objects (and the texts they contain) to survive.

Have you done a similar activity with your students? If so, I'd love to hear how it went and how (if at all) it helped your students think in new ways about the literary (or non-literary) texts at the heart of their studies.

* The Huntington's copy on EEBO is missing its title page and the British Library's copy features inlaid pages (thanks, J. P. Kemble!). The ESTC record for Q1 suggests [A]² (-A1) B-I⁴. Our quartos featured A1 (see below).

** UPDATE: Thanks to Aaron Pratt for letting me know there's a fourth hole in the Trial of Chivalry quarto hiding under the knot. You can access his recent article on stab-stitching in The Library via his website.